# Time points for the simulation

Y = 14 # Years of simulation

times <- seq(0, 365*Y, by = 1)

# Estimates of resistance levels over time

resdata <- insecticide_data_summ |>

filter(RESISTANCE_STATUS == "Confirmed resistance") |>

mutate(mean_mortality = mean_mortality/100) # convert into decimal

# Make a time dependent variable of resistance levels

effr_level <- approxfun(resdata$time, resdata$mean_mortality, n = 365*Y, ties = "ordered", method = "constant", rule = 2)

# SEACR-SEI model

seacr <- function(times, start, parameters, effr_level) {

with(as.list(c(start, parameters)), {

P = S + E + A + C + R + G

M_s = Sm_s + Em_s + Im_s

M_r = Sm_r + Em_r + Im_r

M = M_s + M_r

m = M / P

# Seasonality

seas.t <- amp*(1+cos(2*pi*(times/365-phi)))

# Nets

itn <- itn_cov*itn_use

itn_r <- itn*(effr_level(times)) # Adjust effective coverage of ITNs based on resistance level

# Force of infection

Infectious = C + zeta_a*A # infectious reservoir

lambda.v <- seas.t*a*M/P*b*(Im_r*(1-itn_r) + Im_s*(1-itn))/M

lambda.h <- seas.t*a*c*Infectious/P*(1-itn)

# Differential equations/rate of change

# Insecticide-sensitive mosquito compartments

dSm_s = (1-res)*mu_m*M - (lambda.h)*Sm_s - mu_m*Sm_s

dEm_s = (lambda.h)*Sm_s - (gamma_m + mu_m)*Em_s

dIm_s = gamma_m*Em_s - mu_m*Im_s

# Insecticide-resistant mosquito compartments

dSm_r = res*mu_m*M - (lambda.h)*Sm_r - mu_m*Sm_r

dEm_r = (lambda.h)*Sm_r - (gamma_m + mu_m)*Em_r

dIm_r = gamma_m*Em_r - mu_m*Im_r

# Human compartments

dS = mu_h*P - lambda.v*S + rho*R - mu_h*S

dE = lambda.v*S - (gamma_h + mu_h)*E

dA = pa*gamma_h*E + pa*gamma_h*G - (delta + mu_h)*A

dC = (1-pa)*gamma_h*E + (1-pa)*gamma_h*G - (r + mu_h)*C

dR = delta*A + r*C - (lambda.v + rho + mu_h)*R

dG = lambda.v*R - (gamma_h + mu_h)*G

dCInc = lambda.v*(S + R)

# Output

list(c(dSm_s, dEm_s, dIm_s, dSm_r, dEm_r, dIm_r, dS, dE, dA, dC, dR, dG, dCInc), itn=itn, itn_r=itn_r)

})

}

# Initial values for compartments

initial_state <- c(Sm_s = 5000000, # susceptible insecticide-sensitive mosquitoes

Em_s = 3000000, # exposed and infected insecticide-sensitive mosquitoes

Im_s = 1000000, # infectious insecticide-sensitive mosquitoes

Sm_r = 4000000, # susceptible insecticide-resistant mosquitoes

Em_r = 2000000, # exposed and infected insecticide-resistant mosquitoes

Im_r = 1000000, # infectious insecticide-resistant mosquitoes

S = 3500000, # susceptible humans

E = 350000, # exposed and infected humans

A = 1300000, # asymptomatic and infectious humans

C = 650000, # clinical and symptomatic humans

R = 100000, # recovered and semi-immune humans

G = 100000, # secondary-exposed and infected humans

CInc = 0 # cumulative incidence in humans infected by insecticide resistant mosquitoes

)

# Country-specific parameters should be obtained from literature review and expert knowledge

parameters <- c(a = 0.3, # human biting rate

b = 0.4, # probability of transmission from mosquito to human

c = 0.4, # probability of transmission from human to mosquito

r = 1/7, # rate of loss of infectiousness after treatment

rho = 1/160, # rate of loss of immunity after recovery

delta = 1/200, # natural recovery rate

zeta_a = 0.4, # relative infectiousness of of asymptomatic infections

pa = 0.35, # probability of asymptomatic infection

mu_m = 1/10, # birth and death rate of mosquitoes

mu_h = 1/(62*365), # birth and death rate of humans

gamma_m = 1/10, # extrinsic incubation rate of parasite in mosquitoes

gamma_h = 1/10, # extrinsic incubation rate of parasite in humans

res = 0.2174, # selection pressure, obtained from data

amp = 0.5, # amplitude of seasonality

phi = 200, # phase angle, start of season

itn_use = 0.58, # probability of sleeping under a net

itn_cov = 0.75 # coverage of LLINs in the population at risk

)

# Run the model

out <- ode(y = initial_state,

times = times,

func = seacr,

parms = parameters,

effr_level = effr_level)

# Post-processing model output into a dataframe

df <- as_tibble(as.data.frame(out)) |>

pivot_longer(cols = -time, names_to = "variable", values_to = "value") |>

mutate(date = ymd("2010-01-01") + time)

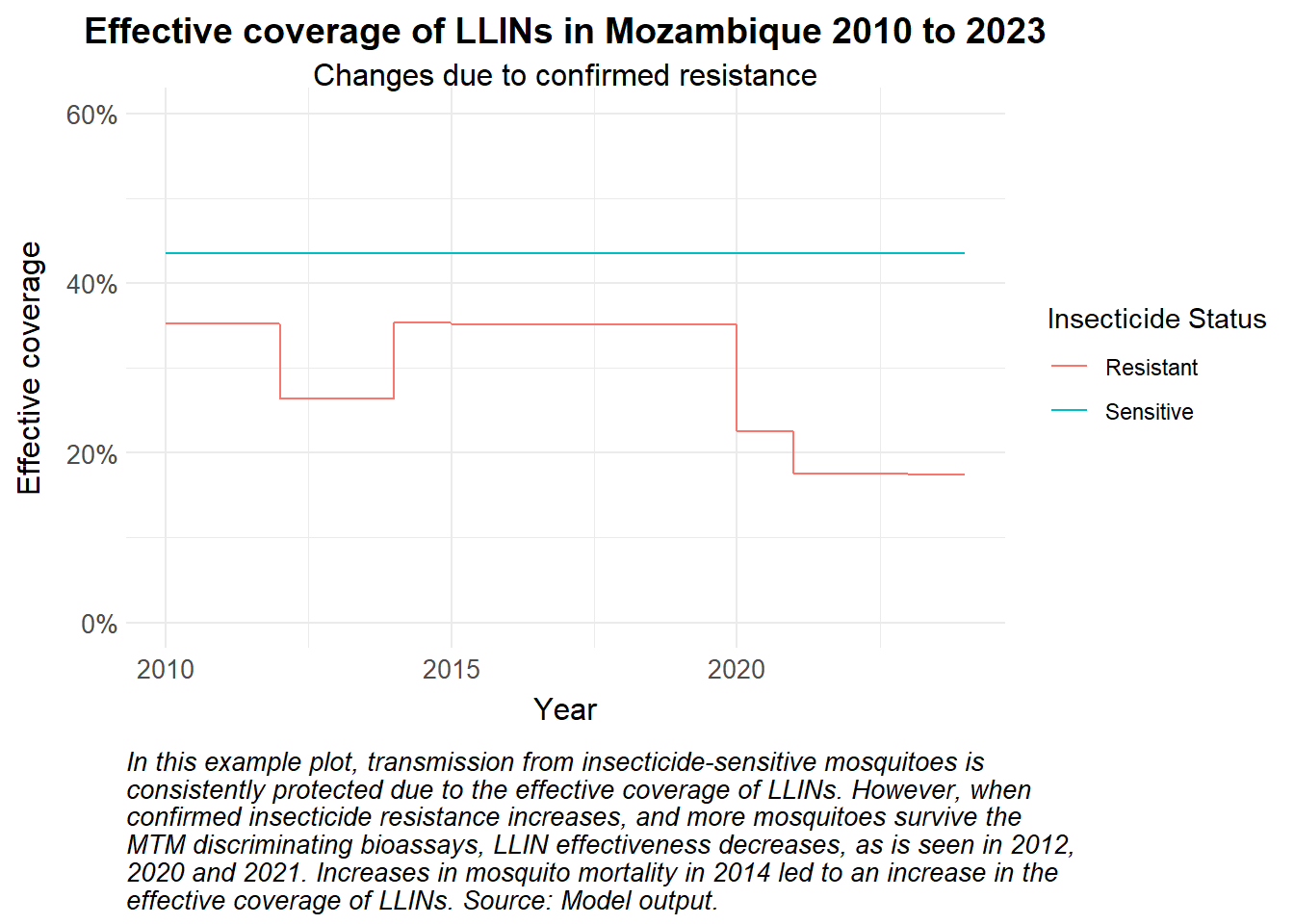

df |>

filter(variable %in% c("itn", "itn_r"), date > "2010-01-01") |>

mutate(`Insecticide Status` = case_when(

variable == "itn" ~ "Sensitive",

variable == "itn_r" ~ "Resistant")) |>

ggplot(aes(x = date, y = value, colour = `Insecticide Status`)) +

geom_line() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent, limits = c(0, 0.6)) +

labs(

x = "Year",

y = "Effective coverage",

title = "Effective coverage of LLINs in Mozambique 2010 to 2023",

subtitle = "Changes due to confirmed resistance",

caption = str_wrap("In this example plot, transmission from insecticide-sensitive mosquitoes is consistently protected due to the effective coverage of LLINs. However, when confirmed insecticide resistance increases, and more mosquitoes survive the MTM discriminating bioassays, LLIN effectiveness decreases, as is seen in 2012, 2020 and 2021. Increases in mosquito mortality in 2014 led to an increase in the effective coverage of LLINs. Source: Model output.")) +

theme_health_radar()